Free fall

Annotations by Ben Wilbrink

Physics is a broad field. In order to reach some efficiency in the study of physics and the design of physics test items, it would be nice to concentrate the effort on one or two physics topics only. The one subject that seems most suitable to this VIP treatment is that of free fall. The history of the subject, that is until Newton's laws, is available in Dijksterhuis (1924) Fall and throw. A contribution to the history of mechanics from Aristotle until Newton [original in Dutch: Val en worp]. The main results also in Dijksterhuis (1950), available in English translation (1961). An important addition to the work of Dijksterhuis concerning Galileo is Stillman Drake (1990), among others on the times-squared law of distances in fall.

The work of Galileo is indeed a turning point in the science of physics, from natural philosophy to experimental science. From the attempt to find causes of natural phenomena, to the attempt to describe them on the basis of experimental observation. From the use of philosophical language to that of mathematics to do the theorizing.

Free fall is a rather simple concept in modern physics, it should be possible for readers not knowing much or anything of physics, to follow the main examples and arguments. Yet many important epistemological problems in science—and therefore also in education—may be illustrated using free fall. The most important problem being the relation between physics and mathematics. Free fall has something to do with gravitation, yet calling gravitation the cause of free fall is name-calling only. Understanding free fall more or less stops at the description of the phenomena, the most succint description being an appropriate mathematical formula. The danger, then, is to suppose that being able to reproduce this formula or apply it in toy-situations is proof of 'understanding' free fall. Have I made myself clear? I fear not. But then the above is my program of action only.

Another example of work in physics done without any understanding of possible 'causes' of the phenomenon, is the discovery of temperature, as described by Hasok Chang in his 2008 book under this name.

Hasok Chang (2004/2007). Inventing temperature. Measurement and scientific progress. Oxford University Press.

Travis Norsen (2005). Lab 2: Galileo's Freefall Experiment. General Physics I, Marlboro College, Fall `05. http://akbar.marlboro.edu/~norsen/courses/2005-2/genphys/lab2.pdf [dead link? 1-2009]

- abstract In this lab you will reproduce an elegant experiment first performed by Galileo. The basic idea is to correlate the height of a dropped ball and the length of a pendulum such that the freefall time for the ball and the time for the released pendulum to reach the vertical are equal. In other words, we use a pendulum as a clock to measure how much time it takes a ball to fall from a given height. Combining the results of this correlation with the pendulum period-length relation discovered in Lab 1 permits a quantitative statement of the law of free-fall, i.e., a statment of the amount of time it takes for an object to fall from a given initial height.

- Uses the desciption by Stillman Drake (1990) of Galilei's experiments

- The experiment is part of a course in general physics, by Travis Norsen, Marlboro College http://akbar.marlboro.edu/~norsen/courses/2005-2/genphys/genphys.html [dead link? 1-2009]. Other experiments are in the same vein.

- "Course Overview: First half of the year-long introductory physics sequence covering the discoveries of Galileo and Newton. Students will be expected to use a traditional physics textbook as a supplemental resource, but class-time and written assignments will focus almost exclusively on actually doing physics. Each week students will perform an experiment to uncover and elucidate some concept or principle of mechanics; weekly papers will report on what was done, how it was done, and what the results mean and imply." Nothing spectacular here, this is what physics instruction should be. How rare is such a course? See http://akbar.marlboro.edu/~norsen/courses/2005-2/genphys/genphys.html#policies [dead link? 1-2009] for the description of the course's 'philosophy.'

E. J. Dijksterhuis (1924). Val en worp. Een bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der mechanica van Aristoteles tot Newton. Groningen: Noordhoff. [Fall and throw. A contribution to the history of mechanics from Aristotle to Newton]

- The book, though written in Dutch, will be useful to the English reader also, for Dijksterhuis has taken special care to give full quotes in the original languages.

E. J. Dijksterhuis (1951/1969). The mechanization of the world picture. London: Oxford University Press.

- This is the translation of his prize-winning 1951 book. In it he uses material from his 1924 study of the history of ideas on free fall.

Stillman Drake (1990) Galileo: Pioneer scientist. University of Toronto Press.

Bas Haring (15 spet 2007). Bas Haring. Kennis-katern De Volkskrant, p. 7.

- Column on Galilei's thought experiment to prove Aristoteles wrong.

- See also the appendix to the dissertation of Denny Borsboom on thought experiments in general, using this one in particular.

- The figure is taken from the daily The Volkskrant, it depicts the tool of the thought experiment designed by Galilei, Haring's variant.

acceleration

The distance

s that a body will fall from rest in a vacuum in time

t seconds is given by the formula

s = ½

gt2. Find its velocity after t

1 seconds and its acceleration.

Solution s = ½

gt2.

Differentiating,

v =

ds/dt =

gt.

Differentiating, α =

dv/dt =

d2s/dt2 =

g.

Hence the velocity when

t =

t1 is

gt1, and the acceleration is a constant

g.

quoted from Claude Irwin Palmer (1924). Practical calculus for home study. McGraw-Hill. p. 93-94.

I suspect it is in itself remarkable to find free fall even mentioned in a textbook on calculus. The quoted example is more or less all that its author has to say on the subject of free fall.

A body falls from rest at a place where

g = 32.2. Find (

a) the velocity at the end of the third second; (

b) the space fallen through in 5 seconds; (

c) the space fallen through in the fifth second.

Ziwet (1893/94, Vol. 1 p. 56)

Galilei, who first discovered the laws of falling bodies, expressed them in the following form: (a) The velocities at the end of the successive seconds increase as the natural numbers; (b) the spaces described during the successive seconds incease as the odd numbers; (c) the spaces described from the beginning of the motion to the end of the successive seconds increase as the squares of the natural numbers. Prove these statements.

Ziwet (1893/94, Vol. 1 p. 56)

"Prove these statements" (box above): that is a mathematical question, not a physical one! About those 'seconds': that is an anachronism. How is it possible for a carefully formulating man like Ziwet to be so sloppy in matters historical? I doubt that Galilei used the concept of velocity [at a particular moment, i.e. in the limit], I will check on that.

A stone dropped into the vertical shaft of a mine is heard to strike the bottom after

t seconds; find the depth of the shaft, if the velocity of sound be given =

c. Assume

t = 4 s.,

c = 332 metres,

g = 980.

Ziwet (1893/94, Vol. 1 p. 56)

Find the velocity with whih the body arrives at the surface of the earth if it be dropped from a height equal to the earth's radius, and determine the time of falling through this height.

Ziwet (1893/94, Vol. 1 p. 60)

The above question is highly artificial, of course. It serves to exercise the somewhat involved formulas of acceleration proportional to the square of the distance (Newton's law of universal gravitation). Today one might shoot a rocket to the specified height, from which it will fall back to the earth, in 1893 such a possibility was science fiction.

Damerow, Peter, e.a. (2004). Exploring the Limits of Preclassical Mechanics: A Study of Conceptual Development In Early Modern Science; Free Fall and Compounded Motion In the Work of Descartes, Galileo and Beeckman. (Sources and Studies In the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences) Springer.

Edwin Danson (2006). Weighing the world. The quest to measure the earth. Oxford University Press.

- About the complexities of free fall in the neighborhood of big mountains.

Alexander Ziwet (1893/4). An elementary treatise on theoretical mechanics. Part I Kinematics. Part II Introduction to dynamics; statics. Part III Kinetics Three volumes. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Acceleration in variable rectilinear motion is treated in paragraph 97 and the following ones. The presentation is highly abstract, starting from what is the most general formulation. Only in par. 112 an example is introduced: 'a body falling in vacuo near the earth's surface.' This kind of description is typical for this textbook, and probably most or all textbooks of physics, of all times. It is guaranteed to chase students away from studying physics. Why not let them find out for themselves, experimenting with free falling objects, the essentials of the physics of the phenomenon? See for an example, using a Galilean setup, here

- Ziwet is not Galileo, Ziwet drains his exercises from all that could make it interesting to students: p. 55: "In the exercises on falling bodies (Art. 114) we make throughout the following simplifying assumptions: the falling body does not rotate; the resistance of the air is neglected, or the body falls in vacuo; the space fallen through is so small that g may be regarded as constant; the earth is regarded as fixed, i.e. we consider only the relative motion of the body with respect to the earth." It is quite evident that Ziwet 'exercises' are mathematical ones, nothing even remotely experimental here!

- Vol. I p. 59 par 188 describes the theory of acceleration inversely proportional to the square of the distance, Newton's law of universal graviation. The description follows the mathematics presented in paragraph 117. The whole physics is rduced to the abstract "It is an empirical fact that the acceleration of bodies falling in vacuo on the earth's surface is constant only for distances from the surface that are very small in comparison with the radius of the earth. For larger distances the acceleration is found inversely rpoportional to the square of the distance from the earth's centre." Is this nonsens, or has Ziwet experiments in mind of freefall in vacuo at sea level, contrasted with some level high in the Alps? The student is not informed of the physical experiments or measurements used to derive the law. What kind of physics education is this, anyhow?

- p. 63 par 125 Retardation due to a resisting medium. This is air resistance, only. Nothing about what might happen in water. No mention of 'displacement' of air itself. No experimental illustrations. For velocities above 420 metres: "For further particulars the reader is referred to special works on ballistics."

f = ma (Newton)

Force equals mass times acceleration. Is this classical formula (a) a law of physics, (b) the definition of force, (c) an axiom formulated by Newton?

Henk J. M. Bos: De zeventiende eeuw — wiskunde aan het begin van de Moderne Tijd. In Machiel Keestra (Red.) (2006). Een cultuurgeschiedenis van de wiskunde. Uitgeverij Nieuwezijds.

- p. 120-121 the basics on free fall. 17th century science studies continuous change processes such as the free fall. Let f = mg, g = gravity constant, an acceleration. The acceleration g is the change in speed v during a small time interval t: dv/dt. Therefore mg = m dv/dt.

The differential equation is gdt = dv, its solution is v = gt: the speed of falling grows proportionally to the falling time t. -

To be able in this way to describe natural processes has been a major achievement of 17th century scientists such as Newton, Leibniz, Huygens and thinkers/mathematicians such as Descartes. It looks a lot like our high school physics, doen't it? The problem, of course, is that the job was not yet finished by being able to apply some analysis and algebra. See, for example, Hanson and Ellis, below. b.w.

Norwood Russell Hanson (1965). Newton's First Law: A Philosopher's Door into Natural Philosophy. In R. G. Colodny. Beyond the edge of certainty. Essays in contemporary science and philosophy (pp.6-28). University Presss of America.

- p. 21, closing sentences: "(...) we have done enough here to suggest that every law within physics is a cornucopea of philosophical perplexities and conceptual excitement. Every such law functions in organizing part of a science's subject matter, in patterning the structure of its arguments and its permissible intellectual moves. And if the discipline which embodies it effectively describes nature, such a law may be said to tell the truth. The fundamental laws of statics and kinematics, of optics and dynamics, of celestial perturbations and microphysical interactions, these contain the most profound challenges to human understanding to be confrontd in our time. And Newton's first law, sometimes characterized as the simplest of the all, turns out to embody challenges as profound as any."

Brian Ellis (1965). The Origin and Nature of Newton's Laws of Motion. In R. G. Colodny. Beyond the edge of certainty. Essays in contemporary science and philosophy (pp. 29-68). University Press of America.

"An impressed force is an action exerted upon a body, in order to change its state, either of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line."

Newton, Principles, p. 2, as translated in Jammer 1957/1999 p. 121.

"Since newton clearly distinguishes between definitions and axioms (or laws of motion), it is obvious that the second law of motion was not intended by Newton as a definition of force, although it is sometimes interpreted as such by modern writers on the foundations of physics. Nor was it meant to be merely the statement of a method of measuring forces. Force, for Newton, was a concept given a priori, intuitively, and ultimately in analogy to human muscular force. Definition IV, therefore, is not to be interpreted as a nominal definition, but as summarizing the characteristic property of forces to determine accelerations."

Jammer 1957/1999, p. 124

Test items

- A straight tunnel is bored through the earth to connect two points A and B on the surface. Show that under certain assumptions, which you should state, the time T to fall freely from A to B is independent of A and B. Caluculate T in minutes, taking the earth's radius to be 64000 km.

-

Comment on the feasibility of a web of such tunnels as a global transportation system.

-

Does a straight tunnel provide the quickest connection between A and B? Discuss briefly.

Thompson 1990, p. 5, #11. The answers: p. 51-52 (click here for the answers to 1. and 2.).

Simulations

For an applet simulating the Galileo setup of rolling balls, see problem number one here: html, click on the link to the Java applet. The applet allows editing of parameters of the experiment. The course was given in 1999 by Larry Gladney, professor of Physics and Astronomy (see his home site)

For an applet simulating the Galileo setup of rolling balls, see problem number one here: html, click on the link to the Java applet. The applet allows editing of parameters of the experiment. The course was given in 1999 by Larry Gladney, professor of Physics and Astronomy (see his home site)

Literature

Nancy J. Nersessian (1992). How do scientists think? Capturing the dynamics of conceptual change in science. In R. Giere: Cognitive models of science. University of Minnesota Press. pdf

- Free fall and Galileo's thought experiment is one of the cases here.

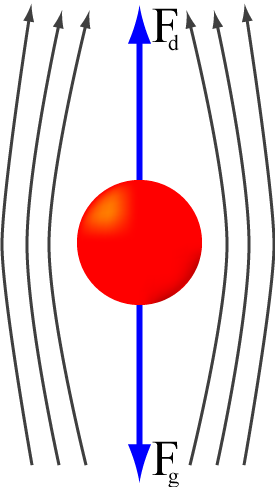

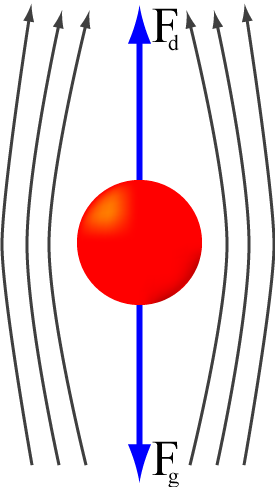

Patrick T. Reardon, Alan L. Graham, Shihai Feng, Vibha Chawla, Rahul S. Admuthe and Lisa A. Mondy (2007). Non-Newtonian end effects in falling ball viscometry

of concentrated suspensions. Rheologica Acta, 46, 413-424. pdf

Patrick T. Reardon, Alan L. Graham, Shihai Feng, Vibha Chawla, Rahul S. Admuthe and Lisa A. Mondy (2007). Non-Newtonian end effects in falling ball viscometry

of concentrated suspensions. Rheologica Acta, 46, 413-424. pdf

- Free fall experiments, yes indeed! Free fall can still be exciting!

- The figure shows the experimental situation. [the 'chart on the right' not shown here]

- I was looking in the rheologica corner because this is a kind of physics, and physical measurement, resembling somewhat the behavioral sciences in their overwhelming problems in measuring whatever they suspect to deserve being measured.

-

Patrick T. Reardon (2003). Constant force and constant velocity experiments in concentrated suspensions. dissertation. free preview

- Stokes' law

-

drag (physics see figure with red ball

drag (physics see figure with red ball - Sir George Gabriel Stokes (1850). On the effect of the internal friction of fluids on the motion of pendulums. [From the Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, Vol. IX. p. [8]

Reprinted in Mathematical and Physical Papers, Sir George Gabriel Stokes and Sir J. Larmor, Vol. 3, 1880-1905] pdf

Aant Elzinga (1972). On a research program in early modern physics. Götegorg: Akademieförlaget.

- Ch. 3: Aristotle's classification of 'mechanical' activity. Par. 3: Falling bodies. p. 47-48. "The beginning of a rupture at the level of theoy is found in the analysis of motion of bodies made by 14th century schoolmen like Oresme. They introduced the notion of exact distance iinto the theory of location and the systematic expression of addition and subtraction of increments of velocity per unit time by use of a rectangular coordinate system. The area under a velocity-time graph was taken to represent distance. A uniform motion was represented by a straight line parallel to the abscissa, and a uniformly accelerated motion by a straight line inclined to the abscissa." The kind of coordinate system as in figures 1.4 and 1.5 of Alonso and Finn's (Dutch translation: vol. 1. Mechanica). :This was certainly a great step away from the Aristotle's non-mathematical theory of localization of bodies in motion, but still in the framwork of Aristotelianism."

- Ch. 4: The struggle between two great world systems and outlooks. Par. 1: The crucial analogy of the stone dropped the mast of the moving boat. p. 58. "Clagett has found the idea of closed mechanical system is already latent in the thought of Buridan and Oresme."

Gerrits, G. C. Gerrits (1939, 1941). Leerboek der natuurkunde. Brill. – 3 delen, linnen, 22e, 18e, 17e druk resp., 249 + 227+254 blz, ingevoegd overzicht deel II 27 blz, idem deel III 24 blz.

- In deel I, par. 41 het hellend vlak ‘Een hellend vlak is ieder vlak, dat een hoek met het horizontale vlak maakt.’ Prachtig. Een abstracte meetkundige figuur met een rond ‘object’ op een helling, een vecor die de zwaartekracht voorstelt, etcetera. Heel abstract dus, in grote vanzelfsprekendheid. Dan volgt een soort definitie van evenwicht:

- “Een lichaam op een hellend vlak is in evenwicht, als de kracht evenwijdig aan de helling aangebracht, zich verhoudt tot de last als de hoogte van het hellend vlak tot de lengte.”

- Dit doet toch wel erg negentiende-eeuws aan, volkomen onbegrijpelijk. Het moet een ramp zijn geweest voor oppervlakkig lerende leerlingen.

- p. 47, meteen volgend op de definitie van evenwicht op een hellend vlak, alsof het er direct iets mee heeft te maken: “Met een hellend vlak, de ‘valgoot’, heeft vrije val. Galileï heeft op deze wijze de vrije val nagegaan en daarbij de beide valwetten gevonden (par. 24 [de vrije val der lichamen]).” De presentatie door Gerrits haalt heden en verleden hopeloos door elkaar: hij verwijst naar Galilei, maar zijn tekst over de vrije val (par. 24) is hedendaagse natuurkunde. Het is m.i. onmogelijk om uit de tekst van Gerrits een idee te krijgen van waar Galilei precies mee bezig was, dus ook van wat zijn betekenis voor de natuurkunde is geweest; of nog anders: hoe natuurkundige inzichten zich o.a. door het werk van Galilei hebben ontwikkeld (waar de didactiek van de natuurkunde zijn voordeel mee zou kunnen doen)

- Fig. 56 is een afbeelding van een goot (zeg een stuk dagoot) dat hellend is geplaatst door aan het ene einde een blok eronder te zetten. Een stevige hellingshoek, overigens, veel groter dan de, ik meen 7 graden die Galilei gebruikte. (Galilei spellen we tegenwoordig zonder trema). Dan volgt de beschrijving van een experiment met die valgoot, dat afwijkt van het door Galilei gedane experiment (zonder dat Gerrits dat meldt):

- “Om de beweging van een kogel langs een helling na te gaan, gebruiken we een gladde goot, die in schuine richting geplaatst wordt en zo tot een hellend vlak gemaakt wordt. Een houten blokje, dat op verschillende plaatsen op de helling kan worden vastgezet, dient als stootblok. We plaatsen dit zé, dat na 1, 2, 3 seconden een gladde, metalen kogel, die aan de bovenkant van de helling wordt losgelaten, tegen dit stootblok komt. Het aantal seconden wordt met een stophorloge bepaald. Meten wij de wegen, die in 1, 2, 3 seconden doorlopen worden, dan blijken deze zich te verhouden als 12 : 22 : 32. De beweging langs de helling is dus eenparig versneld (par. 23). Uit s = ½ at2 kan nu a, de versnelling langs de helling, bepaald worden.

M. Minnaert (1971 (3)). De natuurkunde van 't vrije veld. 3. Rust en beweging. Thieme.

- p. 260 #149 .Vallende lichamen met weinig luchtweerstand. [Falling bodies having little air resistance.]

- p. 261 #150. Snelheid van vallende regendruppels [Speed of falling raindrops]

- p. 264 #151. Vallende sneeuwvlokken. [Falling snowflakes]

- p. 265 #152. Vallend water [Falling water]

- 266. #153. Stand van vallende voorwerpen. [position of falling objects]

C. D. Andriesse (1993/2007). Titan kan niet slapen. Een biografie van Christiaan Huygens. Olympus.

- p. 159-176: Mersenne wrote Huygens about his experiment measuring the heigt a cannon ball uses to drop in one second: 12 feet. In fact, he was measuring g. His twelve feet is about three quarter of the precise value (4.9 meter). Riccioli used a shorter pendulum and found 4.7 meter. Huygens replicated the Mersenne experimment, finding 14 feet, a value definitely different from that of Mersenne. Etcetera. I will have to find articles or books describing the free fall experiments made by Huygens in more detail than Andriesse does in this biography. Andriesse lists the important publications on Huygens' work.

- Zijn posthuum verschenen boek p. 188: Horologium oscillatorium is in vijf delen. "Het tweede deel bestaat uit een reeks voorstellen over de val: eerst de vrije val, dan die langs scheve vlakken en vervolgens die langs gekromde banen. Het loopt uit in het voorstel dat een lichaam dat langs een cycloïdale baan valt steeds in dezelfde tijd zijn laagste punt bereikt, ongeacht het punt op die baan waar de val begint, het voorstel dus dat de cycloïde synchroon is." Dit werk van Huygens is waarschijnlijk een bijzonder fraai voorbeeld van hoe een abstract wiskundig idee bruikbaar blijkt om een stukje natuurkunde van de wereld te beschrijven. Andriesse beschrijft hoe dat zo is gekomen, op uitdaging van Blaise Pascal (p. 155 e.v.). "Een cycloïde is de kromme lijn die een punt op de omtrek van een cirkel volgt als die cirkel over een plat vlak rolt." Zie voor een mooi voorbeeld hier.

http://www.benwilbrink.nl/literature/freefall.htm

http://www.benwilbrink.nl/literature/freefall.htm

For an applet simulating the Galileo setup of rolling balls, see problem number one here: html, click on the link to the Java applet. The applet allows editing of parameters of the experiment. The course was given in 1999 by Larry Gladney, professor of Physics and Astronomy (see his home site)

For an applet simulating the Galileo setup of rolling balls, see problem number one here: html, click on the link to the Java applet. The applet allows editing of parameters of the experiment. The course was given in 1999 by Larry Gladney, professor of Physics and Astronomy (see his home site)

Patrick T. Reardon, Alan L. Graham, Shihai Feng, Vibha Chawla, Rahul S. Admuthe and Lisa A. Mondy (2007). Non-Newtonian end effects in falling ball viscometry

of concentrated suspensions. Rheologica Acta, 46, 413-424. pdf

Patrick T. Reardon, Alan L. Graham, Shihai Feng, Vibha Chawla, Rahul S. Admuthe and Lisa A. Mondy (2007). Non-Newtonian end effects in falling ball viscometry

of concentrated suspensions. Rheologica Acta, 46, 413-424. pdf  drag (physics see figure with red ball

drag (physics see figure with red ball![]() http://www.benwilbrink.nl/literature/freefall.htm

http://www.benwilbrink.nl/literature/freefall.htm